Inspiration

Bronze phallus with bells (tintinnabulum) from Herculaneum.

Combining the male organ with bells doubled its protective powers.

First century B.C.- first century A.D. Bronze, 5 3/4 in. From the Pornographic Collection, Museo Archelogico Nazionale, Napales, Italy.

Joel Peter Witkin, Harvest, Philadelphia, 1984

Toned gelatin silver print, from an edition of 15. 20″ x 16″

Collection Baudoin Lebon & Lunn Ltd.

Joel-Peter Witkin (born September 13, 1939) is an American photographer who lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico. His work often deals with themes such as death, corpses (and sometimes dismembered portions thereof), often featuring ornately decorated photographic models, including people with dwarfism, transgender and intersex persons, as well as people living with a range of physical features. Witkin is often praised for presenting these figures in poses which celebrate and honor their physiques in an elevated, artistic manner. Witkin’s complex tableaux vivants often recall religious episodes or classical paintings

Moche drinking vessel, Terracotta. Circa 100-400 CE on the north coast of Peru.

The eroticism present in this major pottery collection at Museo Larco in Peru evokes desire, attraction and the coming together of the opposing yet complementary forces that enable life to endlessly regenerate. Depicting a well-defined male with an erect phallus spout, the rim of the vessel has been perforated, forcing its user to drink from the phallus.

Kitagawa Utamaro (1753 – 1806), Uta Makura (The Poem of the Cushion), 1788.

Woodblock print.

Shunga (春画) is a type of Japanese erotic art typically executed as a kind of ukiyo-e (floating-world images), often in woodblock print format. While rare, there are also extant erotic painted handscrolls which predate ukiyo-e. Translated literally, the Japanese word shunga means picture of spring; “spring” is a common euphemism for sex.

Shunga, as a subset of ukiyo-e, was enjoyed by all social groups in the Edo period, despite being out of favor with the shogunate. The ukiyo-e movement sought to idealize contemporary urban living and appeal to the new chōnin (merchant) class. Shunga followed the aesthetics of everyday life and widely varied in its depictions of sexuality. Most ukiyo-e artists made shunga at some point in their careers.

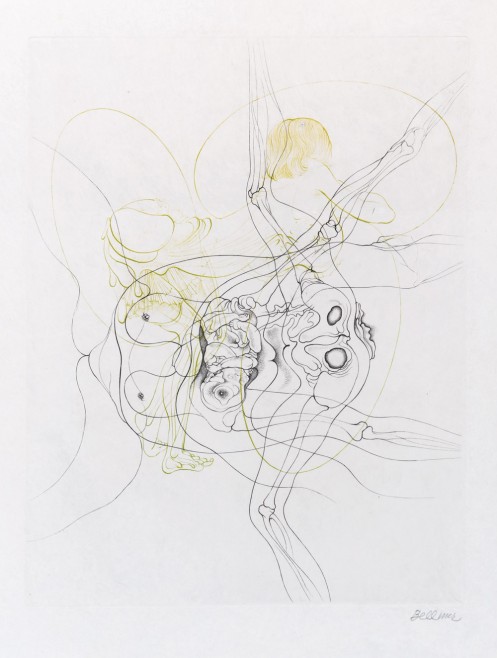

Hans Bellmer (1902 – 1975), Notes Pour La Nouvelle Justine, 1968

Engraving, 27.5 cm x 21.2 cm

Bellmer was a German artist, best known for the life-sized female dolls he produced in the mid-1930s. Historians of art and photography also consider him a Surrealist photographer. Of his own work, Bellmer said, “What is at stake here is a totally new unity of form, meaning and feeling: language-images that cannot simply be thought up or written up … They constitute new, multifaceted objects, resembling polyplanes made of mirrors … As if the illogical was relaxation, as if laughter was permitted while thinking, as if error was a way and chance, a proof of eternity.”

Human-headed winged lion (lamassu), Neo-Assyrian, ca. 883–859 B.C.

Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Gypsum alabaster, Height. 10 ft. 3 1/2 in. (313.7 cm). Stone-Reliefs-Inscribed.

The art of Mesopotamia rivalled that of Ancient Egypt as the most grand, sophisticated and elaborate in western Eurasia from the 4th millennium BC until the Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered the region in the 6th century BC.

An Assyrian artistic style distinct from that of Babylonian art, which was the dominant contemporary art in Mesopotamia, began to emerge c. 1500 BC, well before their empire included Sumer, and lasted until the fall of Nineveh in 612 BC.

The conquest of the whole of Mesopotamia and much surrounding territory by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC) created a larger and wealthier state than the region had known before, and very grandiose art in palaces and public places, no doubt partly intended to match the splendor of the art of the neighboring Egyptian empire. From around 879 BC the Assyrians developed a style of extremely large schemes of very finely detailed narrative low reliefs in stone or gypsum alabaster, originally painted, for palaces. The precisely delineated reliefs concern royal affairs, chiefly hunting and war making. Predominance is given to animal forms, particularly horses and lions, which are magnificently represented in great detail.

Relief of Hathor in the temple of Edfu, Egypt.

From Re-vamping the world: On the return of the Holy Prostitute by Deena Metzger

“Once upon a time, in Sumeria, in Mesopotamia, in Egypt, in Greece, there were no whorehouses, no brothels. In that time, in those countries, there were instead the Temple of the Sacred Prostitutes. In these temples, men were cleansed, not sullied, morality was restored, no desecrated, sexuality was no perverted, but divine. The original whore was a priestess, the conduit to the divine, the one through whose body once entered the sacred arena and was restored. Warriors, soldiers, soiled by combat within the world of men, came to the Holy Prostitute, the Quedishtu, literally meaning “the undefiled one,” in order to be cleansed and reunited with the gods. The Quedishtu or Quadesh is associated with a variety of goddesses including Hathor, Ishtar, Anath, Astarte, Asherah, etc. It is interesting to note, according to Patricia Monaghan in The Book of Goddesses and Heroines, that Astarte originally meant “She of the Womb”, but appears in the Old Testament as Ashtoreth, meaning “Shameful thing.” Despite scripture and orthodox thought, war was seen as separating men from the gods, and one had to be reconnected in order to be able to re-enter society. The body, the sexual act, was the means for re-entry. AS the body was the means, so inevitably pleasure was an accompaniment, but the essential attribute of sexuality, in this context, was prayer. In Pergamon, Turkey, I saw the remains of the Temple of the Holy Prostitutes on the Sacred Way, alongside the other temples, palaces, public buildings. Whatever rites we imagine took place in these other buildings, it is common whether we elevate them as do neo-pagans or condemn them as do Judeo-Christians to associate the Holy Prostitutes with orgies and debauchery. But it is possible that neither view is correct, as each tends to inflate the physical activity and ignore or impugn the spiritual component. Our materialist preoccupation with form blinds us to the content.”

![tintinnabula[1]](https://ayuriart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/tintinnabula1.jpg)

![Lot_13[1]](https://ayuriart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Lot_131.jpg)

![o-SHUNGA-900[1]](https://ayuriart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/o-SHUNGA-9001.jpg)